The Missing Semester: Multi-omics

A WNN graph-based method of joint RNA and protein integration.

Welcome to Module 2: Multi-omics of Bioinformatics: The Missing Semester!

Introduction

While each -omics data modality provides valuable insight, when combined, we can extract comprehensive biological patterns to help us answer complex questions and drive innovation.

Integrating these data types can help us unravel layers of biological complexity and uncover new regulatory programs contributing to phenotypic outcomes (especially in chronic disease).

Ultimately, integration of multi-omics data is a moving target for which a one-size-fits-all approach will not work. Drawing insights from two specific omics requires unique strategies, since each omic has a unique data scale, noise ratio and, hence, its own preprocessing steps. How these omics correlate within the same sample and the same cell is not yet understood. (Source)

There are different types of integration:

Matched - data recorded from the same cell

Unmatched - data recorded from different cells

And:

Horizontal - merging the same modality across multiple datasets

Vertical - merging data from different omics within the same sample

Diagonal - merging different omics from different cells/samples

While data integration can be conceptually challenging, it is practically teachable in a single hands-on example. Therefore, we’ll cover the fundamentals of multimodal integration in this single lesson by integrating transcriptomic and proteomic data from the same cells (aka a matched or vertical integration) using a Weighted Nearest Neighbor (WNN) graph.

Let’s get started.

Data ingest

As always, we import dependencies. Since this is a more involved workflow than our previous lessons, we’ll define variables at the beginning for ease of use downstream and reproducibility:

# bioinformatics

import numpy as np

import scanpy as sc

import anndata as ad

import skmisc

import umap

import muon as mu

from scipy import sparse

from scipy.sparse import csr_matrix

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# data ingest

import os

import tempfile

import requests

import pooch

import tqdm

from pathlib import Path

RNG = 0

np.random.seed(RNG)

sc.settings.set_figure_params(dpi=90)

# ---------- CONFIG ----------

N_NEIGHBORS = 15

RNA_N_PCS = 30

PROT_N_PCS = 10

W_RNA = 0.6 # weight for RNA connectivities

W_PROT = 0.4 # weight for protein connectivities

# ----------------------------First, we’ll download PBMC10k and PBMC5k CITE-seq datasets available from 10X Genomics according to the scvi docs. We will subset to the proteins shared between the two datasets and join them together for downstream integration:

save_dir = tempfile.TemporaryDirectory()

def download_data(save_path: str, fname: str = "CITE-seq_pbmc_10k") -> str:

"""Download the data files."""

if fname == "CITE-seq_pbmc_10k":

hash = "md5:26d53ffe08b5f7d3b28df61b592d51fb"

url = "https://cf.10xgenomics.com/samples/cell-exp/3.0.0/pbmc_10k_protein_v3/pbmc_10k_protein_v3_filtered_feature_bc_matrix.tar.gz"

else:

hash = "md5:9be3d672b0445b944ca06a507c3d780b"

url = "https://cf.10xgenomics.com/samples/cell-exp/3.1.0/5k_pbmc_protein_v3/5k_pbmc_protein_v3_filtered_feature_bc_matrix.tar.gz"

data_paths = pooch.retrieve(

url=url,

known_hash=hash,

fname=fname,

path=save_path,

processor=pooch.Untar(),

progressbar=True,

)

return str(Path(data_paths[0]).parent)To avoid downloading the data locally, we’ve instead created a temporary isolated directory on our computer’s filesystem.

Now let’s download the data defined as two separate paths to that temporary directory:

data_path1 = download_data(save_dir.name)

data_path2 = download_data(save_dir.name, "CITE-seq_pbmc_5k")We’ll read them into memory as two separate MuData objects: one for PBMC5k and one for PBMC10k:

mdata1 = mu.read_10x_mtx(data_path1)

mdata2 = mu.read_10x_mtx(data_path2)And create batch labels to properly identify which samples are associated with their respective parent datasets:

# create batch labels

mdata1.mod["rna"].obs["batch"] = "10kpbmc"

mdata2.mod["rna"].obs["batch"] = "5kpbmc"Inspecting both mdata1 and mdata2 respectively, for sanity:

MuData object with n_obs × n_vars = 7865 × 33555

var: 'gene_ids', 'feature_types'

2 modalities

rna: 7865 x 33538

obs: 'batch'

var: 'gene_ids', 'feature_types'

prot: 7865 x 17

var: 'gene_ids', 'feature_types'MuData object with n_obs × n_vars = 5247 × 33570

var: 'gene_ids', 'feature_types'

2 modalities

rna: 5247 x 33538

obs: 'batch'

var: 'gene_ids', 'feature_types'

prot: 5247 x 32

var: 'gene_ids', 'feature_types'Data pre-processing

You may be wondering why we’ve downloaded two separate PBMC datasets. Why not just use one?

Because in real-world R&D that supports drug discovery and other therapeutic endeavors, multiple experiments are required. This multiplicity introduces a phenomenon called “batch effects.” This effect accounts for some of the complexity of biology, as different experiments are derived from different donor pools, have different sequencing runs, different signal:noise ratios etc.

This is also what makes multimodal data integration inherently challenging.

So we’ll merge the two datasets to simulate a batch effect and to demonstrate the fact that a graph-based WNN model can account for that nuance:

# make variable names unique

mdata1.mod["rna"].var_names_make_unique()

mdata2.mod["rna"].var_names_make_unique()

# filter to shared genes and proteins between the two datasets with inner join

rna_c = ad.concat([mdata1.mod["rna"], mdata2.mod["rna"]])

rna_c.obs_names_make_unique()

prot_c = ad.concat([mdata1.mod["prot"], mdata2.mod["prot"]])

prot_c.obs_names_make_unique()

mdata = mu.MuData({"rna": rna_c, "prot": prot_c})We did a few things in the above code:

Made the gene names in each

.modmodality unique (var_names_make_unique()will append suffixes i.e _1, _2 as appropriate)Concatenated both PBMC5k and PBMC10k RNA modalities

Above for the protein modalities

Wrapped them both into a MuData container

Upon inspection, we see we’re now working with a single MuData object:

MuData object with n_obs × n_vars = 13112 × 33555

2 modalities

rna: 13112 x 33538

obs: 'batch'

prot: 13112 x 17Dimensionality reduction with PCA

Good software engineering practice (which makes for good bioinformatics practice) involves sprinkling in checks or assertions into code to preemptively catch errors before they happen. Let’s first check to make sure both RNA and protein modalities are present in our MuData container:

assert 'rna' in mdata.mod and 'prot' in mdata.modGreat. Now we can separate each modality for easier handling later on:

# separate modalities

rna = mdata.mod['rna']

prot = mdata.mod['prot']We need to reduce the dimensionality of our data before calculating neighbors for our WNN graph:

# ensure PCA is computed for each modality (otherwise compute it)

# RNA: expect obsm['X_pca'] or compute it

if 'X_pca' not in rna.obsm:

sc.pp.highly_variable_genes(rna, n_top_genes=4000, subset=True, flavor='seurat_v3')

sc.pp.scale(rna, max_value=10, copy=False)

sc.tl.pca(rna, n_comps=RNA_N_PCS)

rna.obsm['X_pca'] = rna.obsm['X_pca'] # explicit keyHere, we’re checking first if PCA embeddings are present in the RNA modality (by looking for X_pca in .obsm of RNA) and if it isn’t, we select the most highly variable genes, scale the data to 0 and compute the principal embeddings which we explicitly save to .obsm['X_pca'].

We do the same for the protein mod, except we first check for CLR-transformed data. If those aren’t present, we define a Centered Log-Ratio transformation function and save the transformed protein data to .obsm['protein_clr']:

# protein: expect prot.obsm['X_pca'] (we'll compute PCA on CLR)

if 'protein_clr' not in prot.obsm:

# simple CLR transform (for visualization/PCA)

def clr(mat):

if sparse.issparse(mat):

mat = mat.toarray()

gm = np.exp(np.mean(np.log1p(mat), axis=1))

return np.log1p(mat / gm[:, None])

prot.obsm['protein_clr'] = clr(prot.layers.get('counts', prot.X))Now we can compute PCA embeddings on the CLR-transformed data, and deposit those in .obsm['X_pca']:

if 'X_pca' not in prot.obsm:

from sklearn.decomposition import PCA

pca_prot = PCA(n_components=min(PROT_N_PCS, prot.obsm['protein_clr'].shape[1]-1))

prot.obsm['X_pca'] = pca_prot.fit_transform(prot.obsm['protein_clr'])Joint WNN graph computation

The goal here is to generate separate neighborhood graphs: one for RNA and one for protein, then integrate them into a single weighted graph.

Let’s compute a nearest neighborhood graph for the RNA modality using the PCA embeddings stored in .obsm['X_pca']:

sc.pp.neighbors(rna, n_neighbors=N_NEIGHBORS, use_rep='X_pca')This creates two objects:

rna.obsp['connectivities']: sparse weighted adjacency matrix representing graph connectivity (i.e., the strength of connection between cells)rna.obsp['distances']: sparse matrix of distances between neighbors

To minimize confusion, we’ll assign both objects to new modality-specific keys and delete the original ones:

rna.obsp['connectivities_rna'] = rna.obsp['connectivities'].copy()

rna.obsp['distances_rna'] = rna.obsp['distances'].copy()

# remove defaults just in case

del rna.obsp['connectivities']

del rna.obsp['distances']

del rna.uns['neighbors']Now we’ll compute a neighbor graph for the protein modality:

# calculate protein neighbors

sc.pp.neighbors(prot, n_neighbors=N_NEIGHBORS, use_rep='X_pca')

prot.obsp['connectivities_prot'] = prot.obsp['connectivities'].copy()

prot.obsp['distances_prot'] = prot.obsp['distances'].copy()

del prot.obsp['connectivities']

del prot.obsp['distances']

del prot.uns['neighbors']WNN graph integration

Okay. We now have neighbor graphs for both our RNA and protein—let’s integrate them.

Before we do anything else, we need to make sure that the cells in rna and prot are identically aligned; otherwise adding their connectivity matrices would be meaningless:

assert (rna.obs_names == prot.obs_names).all(), "Cell order mismatch — align modalities first"Then we extract both connectivity matrices and force them into a Compressed Sparse Row (CSR) format for efficient operations downstream:

C_rna = rna.obsp['connectivities_rna']

C_prot = prot.obsp['connectivities_prot']

C_rna = C_rna.tocsr() if sparse.issparse(C_rna) else csr_matrix(C_rna)

C_prot = C_prot.tocsr() if sparse.issparse(C_prot) else csr_matrix(C_prot)Finally we can combine the neighborhood graphs into a single weighted multimodal graph. Importantly, muon’s mu.pp.neighbors() does this exactly and abstracts away the math. But we’ll do the operation by hand here to get a better understanding of what’s happening under the hood:

W = W_RNA * C_rna + W_PROT * C_protWe’ve now calculated a weighted sum of our two components, RNA and protein. Recall that we defined W_RNA (0.6) and W_PROT (0.4) at the very beginning. These are weights, slightly biased towards RNA per literature standard.

To ensure our integrated graph is uni-directed aka the connectivity is mutual, we’ll first force symmetry, then scale each row such that the sum of weights = 1:

W = (W + W.T) / 2.0

row_sums = np.array(W.sum(1)).flatten()

row_sums[row_sums == 0] = 1.0

Dinv = sparse.diags(1.0 / row_sums)

W = Dinv @ WNow we can store our graph into a scanpy-ready CSR format:

rna.obsp['connectivities_wnn'] = W.tocsr()And convert the connectivities into a distance-like matrix as a placeholder for UMAP and the like:

D = sparse.eye(W.shape[0], format='csr') - W

rna.obsp['distances_wnn'] = D.tocsr()Visualization

Now for fun.

In preparation for my favorite part: visualization, let’s create a dictionary of neighbor metadata:

rna.uns['neighbors_wnn'] = {

'connectivities_key': 'connectivities_wnn',

'distances_key': 'distances_wnn',

'params': {'n_neighbors': N_NEIGHBORS, 'method': 'wnn'}

}This will make it easier for us to tell scanpy which key in our MuData object to use for rendering a UMAP.

Now we can go ahead and compute the UMAP from our weighted neighbors:

# compute UMAP from weighted neighbors

sc.tl.umap(rna, neighbors_key='neighbors_wnn')

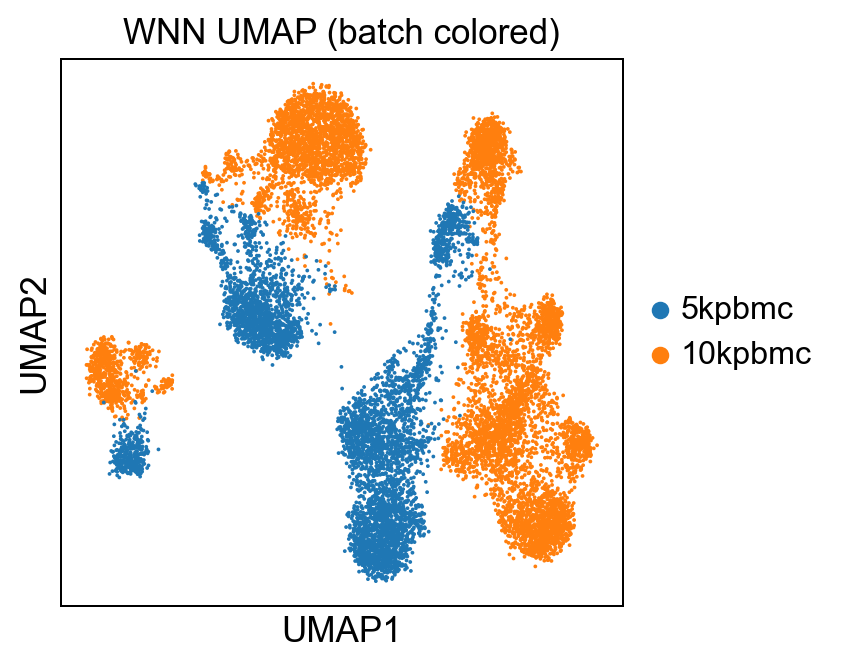

sc.pl.umap(rna, color='batch', title='WNN UMAP (batch colored)')Which yields:

As well as running a leiden clustering on the weighted connectivities:

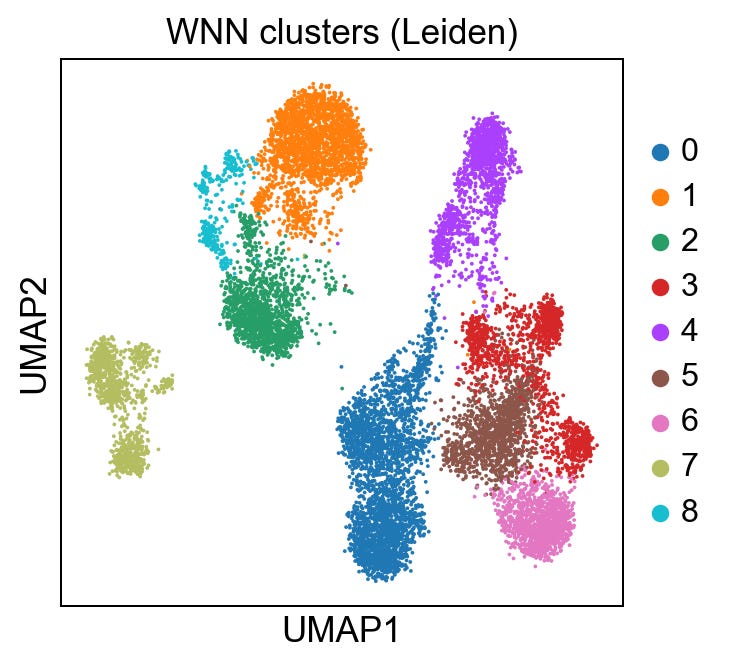

# clustering using WNN graph

rna.obsp['connectivities'] = rna.obsp['connectivities_wnn']

sc.tl.leiden(rna, key_added='leiden_wnn', resolution=0.5, neighbors_key='neighbors_wnn')

sc.pl.umap(rna, color='leiden_wnn', title='WNN clusters (Leiden)')Giving us:

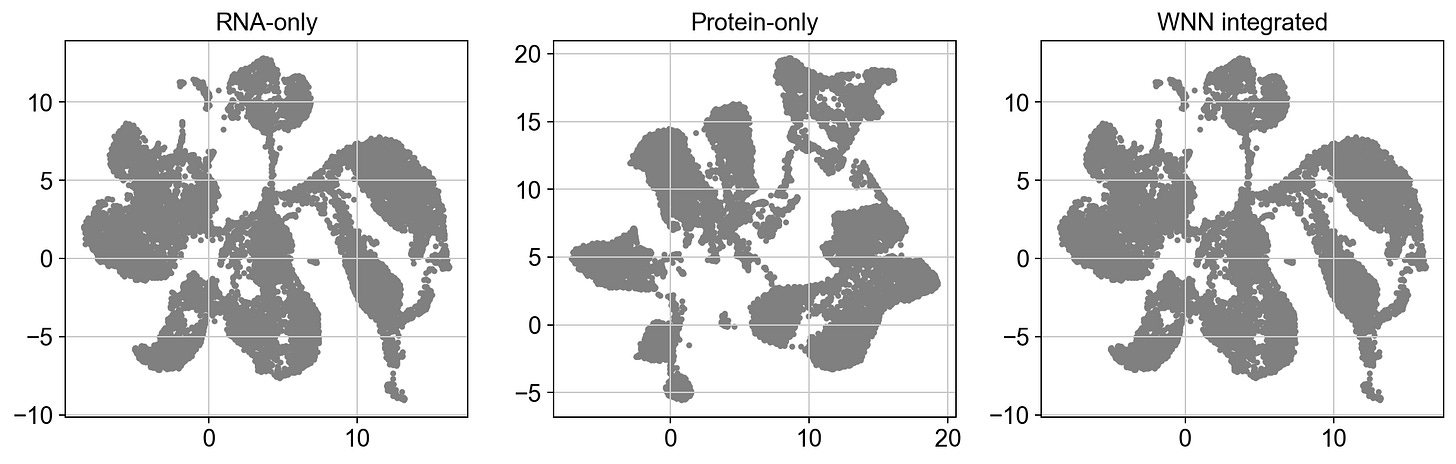

I am going to skip over the technical details a bit for brevity, but to help us evaluate the integration, let’s generate 3 more UMAPs:

RNA-only

Protein-only

WNN-integrated

These will allow us to visualize modality-specific structure, assess the success of the integration and serve as an entry-point for identifying any modality-specific artifacts:

# RNA-only UMAP

sc.pp.neighbors(rna, use_rep='X_pca', n_neighbors=N_NEIGHBORS) # builds rna.obsp['connectivities']

sc.tl.umap(rna)

rna_umap = rna.obsm['X_umap']

# explicitly define dictionary for protein neighbors

prot.uns['neighbors'] = {

'connectivities_key': 'connectivities_prot',

'distances_key': 'distances_prot',

'params': {

'n_neighbors': N_NEIGHBORS,

'method': 'umap'

}

}

# protein-only: reattach connectivities to prot and umap

prot.obsp['connectivities'] = prot.obsp['connectivities_prot']

prot.obsp['distances'] = prot.obsp['distances_prot']

sc.tl.umap(prot, neighbors_key='neighbors')

prot_umap = prot.obsm['X_umap']

# WNN UMAP we stored as 'X_umap' on rna when computing with `neighbors_key='neighbors_wnn'`

wnn_umap = rna.obsm['X_umap']

# quick plotting

fig, axs = plt.subplots(1, 3, figsize=(12, 4))

axs[0].scatter(rna_umap[:,0], rna_umap[:,1], s=6, c=mdata.obs['batch']); axs[0].set_title('RNA-only')

axs[1].scatter(prot_umap[:,0], prot_umap[:,1], s=6, c=mdata.obs['batch']); axs[1].set_title('Protein-only')

axs[2].scatter(wnn_umap[:,0], wnn_umap[:,1], s=6, c=mdata.obs['batch']); axs[2].set_title('WNN integrated')

plt.tight_layout()We get:

At an obvious glance, our WNN integrated plot looks eerily similar to our RNA plot. Because of this, we can say with somewhat certainty that the integration is dominated by RNA; which is less a question of that being good or bad, and moreso whether the data supports that hypothesis.

If our protein-only graph looked similar to the RNA graph, we could hypothesize that our protein features correlate strongly with our RNA features, so adding protein measurements didn’t add anything meaningful. But that isn’t the case.

So what do you think? Recall that our RNA and protein weights are slightly biased towards RNA. I challenge you to consider how adjusting the weights might shift these results. Additionally, explore the original dataset. Here’s another hint: we originally did an inner join on two datasets which wound up only sharing 17 proteins, compared to ~30,000 genes.

Our modality features are very obviously highly imbalanced. And our plots support that.

Which is a good thing!

Integration-only genes

Finally, let’s do a side-by-side marker gene comparison between clusters found using the RNA-only neighbors vs. the WNN-integrated neighbors, to see what extra biological information the integration adds. Step-by-step we’ll:

Cluster cells using RNA only

Find marker genes for RNA only

Find marker genes for WNN clusters

Pull the top marker genes

Compare the RNA-only vs WNN sets

# RNA-only clustering

sc.tl.leiden(rna, key_added='leiden_rna', resolution=0.5) # using RNA-only neighbors

# rank genes in RNA-only and WNN clusters

sc.tl.rank_genes_groups(rna, groupby='leiden_rna', method='wilcoxon', key_added='rna_markers')

sc.tl.rank_genes_groups(rna, groupby='leiden_wnn', method='wilcoxon', key_added='wnn_rna_markers')

# get top N marker names for each cluster

def top_gene_set(adata, key, n=30):

df = sc.get.rank_genes_groups_df(adata, group=None, key=key)

top = df.groupby('group')['names'].apply(lambda s: list(s)[:n]).explode().tolist()

return set(top)

rna_top = top_gene_set(rna, 'rna_markers', n=20)

wnn_top = top_gene_set(rna, 'wnn_rna_markers', n=20)

integration_only_genes = wnn_top - rna_top

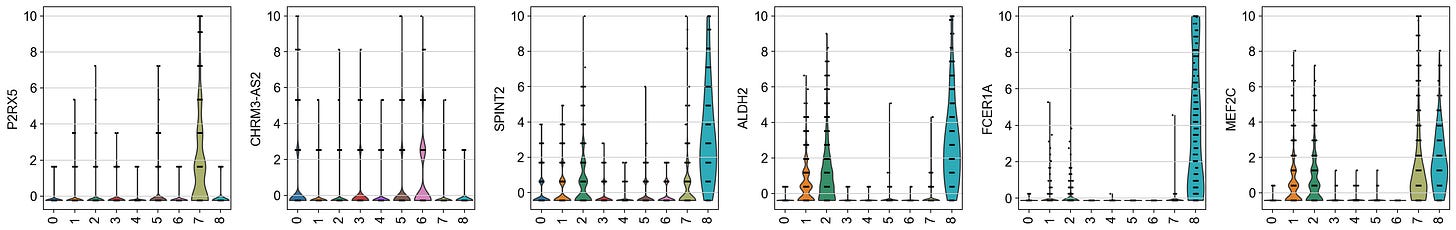

print("Example integration-only genes:", list(integration_only_genes)[:20])Now to plot the top 6 interaction-only genes:

# plot a gene that is integration-only

ex = list(integration_only_genes)[:6]

if ex:

sc.pl.violin(rna, keys=ex, groupby='leiden_wnn', rotation=90, size=2)And we get:

This serves as a check for whether integrating protein data into the neighbor graph changes which genes show up as top markers. Those additional markers might be subtle RNA features that only become important once we account for protein similarities in clustering.

Conclusion

We are in an era of atlas-scale multimodal data, acquired from millions of cells. Successful data integration has the potential to reveal biological function at a resolution yet unseen.

But multi-modal integration is hard.

It’s hard because biology is complex. It remains a challenge to capture modality-specific nuances (like scale, noise:signal ratio, pre-processing, batch effects etc.) and represent those in a single dimension i.e., in a single cell or sample. Not to mention, the most abundant protein may not correlate with high gene expression. This correlation (or lack thereof) makes integration difficult.

Be that as it may, this workflow is a gentle introduction to multimodal integration. Note that there are far more advanced (and perhaps more performant) methods out there like using TotalVI for joint probabilistic modeling, but those are less interpretable.

Though if you want to give those a shot based on this framework, go for it!

In our next lesson, we will take all we’ve learned about bioinformatics data types and multi-modal integration to scale, with an introduction to distributed computing and workflow engineering.

All code and supporting material here.

Thanks. That's quite a unique post on increasingly important topic. Double thanks for doing biology analysis in Python

Thank you so much.